When we got our first cameras, whether it was a little Box Brownie in the 1950s or an iPhone 11 in the 2020s, there is no hesitation about what to photograph. We point it at our families, our pets, our friends, ourselves and click away. We photograph our vacations and special events. We capture moments of time that are bits of life. Before long, though, many of us begin to think those familiar subjects are not enough. We long to make photographs that stand out, that are more important, more beautiful, more exciting.

What can we count on to provide more exciting subjects to photograph?

“If only I could go someplace exotic, like Paris or the Galapagos Islands. Then I could make some great pictures.”

“If only I could get a back-stage pass to the new Rolling Stones concert tour. Then I could do some REAL photography.”

Deep down inside we know that the subject is not what makes our photos great – though great subjects can’t hurt. It is how we see and think and feel that matters. And if we go to those places and events without having trained ourselves to be visually aware, then our pictures will be no more than ordinary.

So, how do we go about training ourselves to see visual possibilities all around us?

-

Learn to see what the lens transmits to the camera viewfinder – especially at the edges of the viewfinder frame. Beginners stick the subject in the middle of the frame. Masters are acutely aware of the edges of the image and the new relationships created by the frame.

A Distant Vista, 2019 ©2019 Kent Miles / kent@kentmiles.com

A Distant Vista, 2019 ©2019 Kent Miles / kent@kentmiles.com

- Pay attention to Light – the quality, the direction, the color, values and contrast, and the amount of light. Shadows can often be more interesting than the objects casting those shadows.

-

Look for gesture and expression – not just in people, but in landscapes, cityscapes, skies, water. Gesture and expression give meaning to the images we make and enable others to emotionally connect to our images.

Smiling Rock Near Lone Pine, California ©1989 Kent Miles / kent@kentmiles.com

Smiling Rock Near Lone Pine, California ©1989 Kent Miles / kent@kentmiles.com

-

Stop naming the things we look at. If our default mode is to look at the named object, then we won’t see the unnamed forms and spaces that are right in front of us that we could utilize to make something profound and evocative and our own. Sometimes the names we use are the pictures we have already seen. If we go to the Snake River Overlook at Grand Teton National Park you will find plenty of photographers there attempting to capture the same wonderful image Ansel Adams shot in 1942. Most of us are not seeing the scene. In our mind’s eye, we just see Ansel’s iconic image and want to make the same photograph. We are not seeing new possibilities, only that which has already been done superbly. If we just try to reshoot Ansel’s photo, our originality is doomed. It takes real effort to suspend the naming process and emphasize the seeing process.

Snake River Overlook, Grand Teton National Park Ansel Adams, 1942

Snake River Overlook, Grand Teton National Park Ansel Adams, 1942

- All photographs start with objective reality, but no photograph IS the objective reality. Once we make an image, that image becomes a new, separate reality. Its effectiveness as a photograph will be determined by whether the viewer is emotionally moved by it. Richard Avedon said “All photographs are accurate. None of them is the truth.” Photographs can record information with great accuracy, but a photograph of my wife is not my wife.

- Don’t forget to turn around. Try looking at this one-minute Awareness Test. I think you will find it amusing and informative. It demonstrates just how powerful our ability to concentrate can be. Remember, we’ll never see what is behind us by staring twice as hard at what is in front of us. (From Roger von Oech’s Creative Whack Pack).

- Look for things that look like other things. Objects that look like faces or like letters or like figures or animals. Ernst Haas made a wonderful image of fresh snow along a creek bank, called Snow Lovers 1964. The image is no longer just a record of what a snowbank looks like. It is a sensual evocation of the elegance of the human form. “Photography is a transformation, not a reproduction,” he said. We can consciously choose to ask ourselves “What does this look like? What do I see?” Before long we reach the point where we are always paying attention to what the world around us looks like without slowing down to ask these questions.

Snow Lovers © 1964 Ernst Haas / Magnum Photos

Snow Lovers © 1964 Ernst Haas / Magnum Photos

I give my students a couple of assignments to cultivate their ability to increase visual awareness. One of these is to photograph found objects that look like the letters and numbers that we use every day, A-Z plus 0-9. (No fair photographing actual numbers and letters.) The idea is to photograph things in a way that makes those things look like letters and numbers. At first, it is a challenge to make the cognitive shift, but after a while, we start to see letters and numbers everywhere. I challenge you to find and photograph things that look like all the letters and digits. Create your own illustrated alphabet.

Alphabet #2 ©2019 Kent Miles / kent@kentmiles.com

Alphabet #2 ©2019 Kent Miles / kent@kentmiles.com

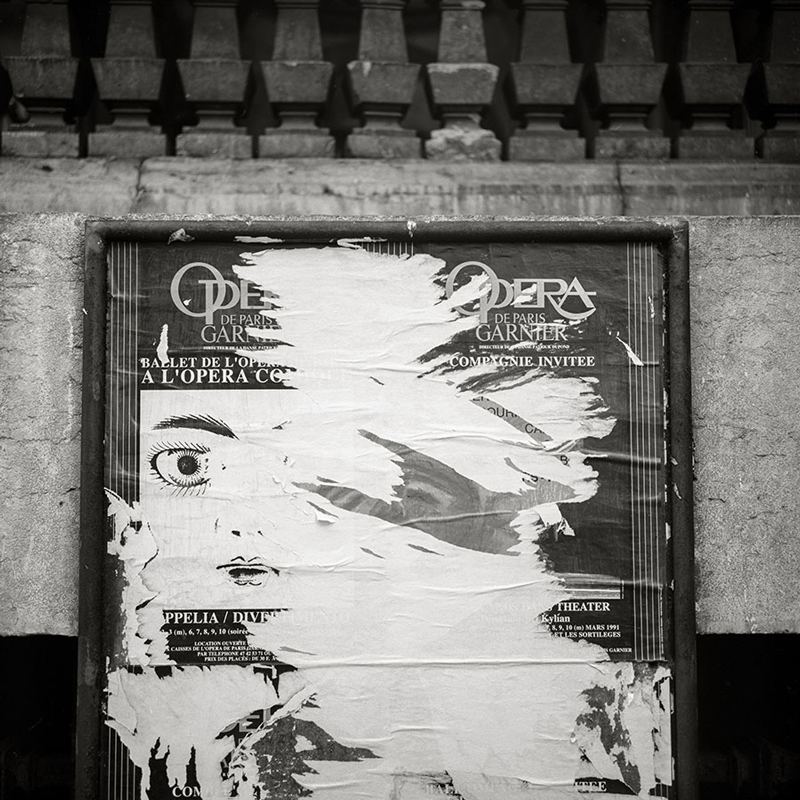

A second assignment is to photograph things that look like faces. In 1997 the brothers Franco̧is and Jean Robert did a book called Face to Face which is a beautiful, whimsical, black and white exploration of this. In 2001 Franco̧is came out with a second book, in color, titled "Faces."

Face to Face, Franco̧is & Jean Robert, 1997 Faces, Franco̧is Robert, 2001

Face to Face, Franco̧is & Jean Robert, 1997 Faces, Franco̧is Robert, 2001

These assignments increase our ability to see things that look like other things. Seeing recognizable objects or patterns in otherwise random or unrelated objects or patterns is called pareidolia. Everyone experiences it from time to time. But it is especially useful for those of us who want to increase our visual awareness, who deeply want to get better at making interesting and effective images.

Try it, you’ll like it.

I’d love to hear and see your responses to this post. Pictureline will select the best written and visual responses to receive a signed print from me. The offer ends when the next blog entry is posted. Good luck!